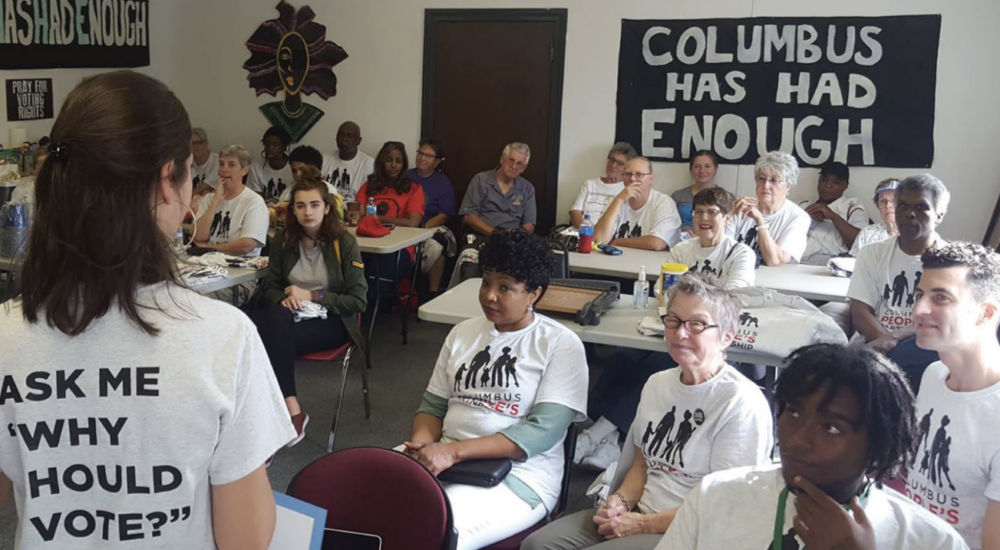

Creating a Community Controlled Local Economy Led by People of Color

Cassandria Campbell had just moved home to Roxbury after earning a degree in urban planning. Frustrated by the lack of fresh food options in her neighborhood – and in low income communities, generally – she and organic farmer Jackson Renshaw launched Fresh Food Generation.

Their catering business, café and particularly their food truck, is a welcome change for people typically without access to healthy menus. The truck’s Latin and Caribbean fare is culturally relevant, earning high praise from residents delighted to be eating the foods they grew up with. Ingredients are sourced from local farms, and prices are kept affordable, competing with nearby restaurants and sub-shops. The business hires from within communities they serve, and operates a grab-and-go breakfast and lunch portal with Dot House, a licensed health center serving non-or-underinsured families in Dorchester.

Campbell and Renshaw’s belief that people should eat well regardless of where they live or how much money they make, is taking hold and getting noticed. So too is their skill at creating synergy between an array of community partners. Recently, they were one of five businesses which the celebrated Boston Ujima Project named as “essential to the fabric of the community.”

Ujima (oo-JEE-mah), the Swahili word for work and responsibility, was formed in 2016 with the intent of building a community controlled economy in Boston’s working class neighborhoods of color. Boston has one of the biggest racial wealth disparities in the country. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, the median net worth of white households is $247,500 compared to just $8 for black households.

Ujima is officially the first democratic investment fund in the county. Instead of depending on conventional financial institutions, they invite people to pool their assets, creating a “top down” control of finances. With as little as $50, current and displaced working class Boston residents, grassroots partner organizations, community business owners and their employees can become voting members. Regardless of the investment amount, Ujima adheres to a “one member, one vote” rule. Others outside the community can become Solidarity non-voting members by investing as little as $100.

Ujima has not issued their first formal investment yet, but they’ve spent the past year extensively preparing – holding community assemblies, conducting online polling, and hosting weekly meetings with their 400 plus members. They shored up unapologetic standards: no staff can earn more than five times the lowest paid employee; businesses must abide by fair work week policies, must be 50 percent minority owned and 60 percent minority staffed. They developed clear informative questions to guide members before voting on investments, including: “What business in your neighborhood do you love?”

While still raising capital from investors and institutions from across the country, Ujima held a Pilot Investment Day, when members voted to support five local black and immigrant businesses through the

Kiva Investment platform. In addition to Fresh Food Generation, they chose the Bowdoin Bike School – a bike shop inspiring local families to find health and freedom in cycling, and a graphic designer who is planning to help new community entrepreneurs market their services.

Ujima is just getting started, already helping people pursue their dream, while strengthening their communities in the process.

Ujima, a current Solidago partner and grantee, is a democratically governed organization with a mission to build a community controlled economy in Boston working class communities of color. To learn more, visit: www.ujimaboston.com.

Photo courtesy of Fresh Food Generation